=======================================================

MEETINGS

No meeting this month, but stay tuned — website, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn — for info on the next meeting in August.

-----

No meeting this month. Going fishing! Check back in August.

-----

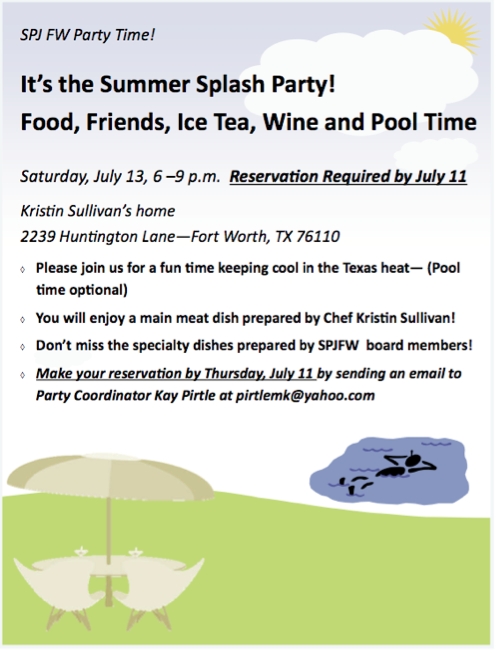

It’s all about the communicators party. Gaze upon the invitation above.

=======================================================

STRAIGHT STUFF

IABC/PRSA local update: The Dallas chapters of IABC and PRSA are happy-hour networking Wednesday, July

17, 5:30-7:30 p.m. at AMS Pictures Studios. Open to members and nonmembers.

Members attend free with registration by July 16; guests $10. Info here.

PRSA local update: This Month in PR/Marketing History (by Jeff Rodriguez). If you paid attention in school, you know that the infamous “Monkey Trial” of high school teacher John Scopes was instrumental in helping advance evolution over creationism. What you didn’t learn in school was that the trial also was a coup for public relations.

It all began in March 1925, when Tennessee voted to outlaw the teaching of

evolution — or more specifically, the teaching of a common ancestry between apes and

humans. The American Civil Liberties Union bought an ad in the Chattanooga

paper, offering to defend any Tennessee schoolteacher who was charged with

violating the new law.

The ad caught the attention of one George Washington Rappleyea, who managed a coal and iron works company in tiny Dayton, Tenn., population

2,000. Rappleyea was a native New Yorker, a Methodist and a supporter of

evolution theory. But he also was a businessman. He arranged a meeting at the

drugstore with the town’s leaders to propose — and everyone agreed — hosting the trial in Dayton as a way to stimulate the struggling local economy.

All they needed was someone to prosecute.

That would be John Scopes, a native Texan who had lived in Wisconsin and Illinois and graduated from the

University of Kentucky. He came to Dayton to coach the high school football

team and was currently filling in for the biology teacher. A local boy was

dispatched to summon Scopes, who was found playing tennis.

Initially reluctant, he came around to the idea, perhaps because he didn’t intend to live there long. He also liked his chances in court. "If you can

prove that I've taught evolution and that I can qualify as a defendant,” he reportedly told the group, “then I'll be willing to stand trial.”

Famed orator William Jennings Bryan agreed to represent the state. A champion of the common man, he was concerned

that Darwinism might be used in support of racial bias. And he had a past with

Scopes: Six years previous, he had spoken at Scopes’ high school commencement, and he recalled how the young man laughed at him.

Bryan’s involvement enticed Clarence Darrow, probably the most famous defense attorney alive at the time. He, too,

championed the common man — he helped organize the local Populist Party and had represented woodworkers and

miners — but had little use for creationism.

The Dayton leaders were delighted. Rappleyea even asked British novelist H.G. Wells to join the defense team, despite Wells being neither an American nor a lawyer.

After all, good PR is good PR.

The trial began July 10. Visitors flocked to Dayton, and 500 additional seats were added to the

courtroom. Loudspeakers blared outside and in auditoriums around town, and

chimpanzees performed on the courtyard lawn. It was, quite literally, a circus.

More than 200 reporters descended on the town, including from The New York Times

and two London papers, plus more than 20 telegraphers and two cameramen.

Chicago radio station WGN did a live broadcast, the first ever in the U.S. The

Baltimore Sun’s acerbic H.L. Mencken, a racist and a snob, called the Daytonites “morons.” Sensing an opportunity to attack religion, it was he who approached Darrow

about taking on Bryan.

Thus the stage was set. But the “trial of the century” turned out rather mundane. The highlight was when Darrow called Bryan to

testify, thus to embarrass Bryan and ridicule his beliefs. The jury, after

talking less than 10 minutes in the hallway, convicted Scopes, even though he

taught from a state-approved textbook. The conviction would be overturned on a

technicality.

For Darrow, the trial brought renewed fame. A few months later, he successfully

defended a black man whose family had been threatened by a mob after the family

moved to an all-white neighborhood. Meanwhile, the ACLU tried to mount another

challenge to the Tennessee law but couldn’t find anyone else willing to be prosecuted. The law stood until 1967.

Bryan, 65 and a diabetic, died five days after the trial. In his lifetime he

spoke passionately against war, monopolies and elitism and in support of

Prohibition, pacificism and Christianity. Some scholars consider his death a

bigger setback to fundamentalism than the trial.

As for Scopes, he accepted a graduate scholarship at the University of Chicago.

He avoided notoriety, except for when he confessed to a reporter that he never

actually taught the evolution lesson and, further, that the students who

testified against him had been coached by his own lawyers.

Around 1937, Rappleyea moved back north, where he enjoyed a long career in the

boating industry. Tiny, struggling Dayton reverted to being tiny and

struggling. The town today has less than 10,000 people, who each summer

celebrate their “Scopes Festival” with scant national attention.

While Rappleyea’s scheme failed on one level, it scored wildly on another. All the publicity,

particularly Mencken’s vitriolic writing, helped turn the tide against fundamentalist doctrine in

public schools, a tide that would gain momentum in the years to come (despite

fierce resistance in Texas).

The scheme also bolstered the status of public relations as an industry. As more

people appreciated its potential, PR began to be seen as a real profession — and not just a bunch of monkey business.